Table of Contents

One morning, I saw an old rugby mate Stuart McInally, had left his post as Captain of Scottish rugby to pursue his dream of becoming a commercial airline pilot.

I never knew this about him so I dropped him a call and he told me that actually “rugby got in the way of my first dream to become a commercial airline pilot”. What an incredible perspective, especially given he had reached the pinnacle of his career in rugby.

I was immediately hooked and now over a year later, I am well on my way to getting my Private Pilots License (PPL). Unsurprisingly, I’ve learnt a lot about being a pilot but also lessons that have significantly helped me sharpen my tools as a cyber security expert.

Learning to fly is both exciting, and unforgiving.

There are no shortcuts at 3,000 feet, no room for complacency when weather shifts, instruments fail or engines fail. As someone who is both building a cyber security company and currently working towards getting my pilots license, I’ve realised that learning to fly is teaching me much more about cyber security than I ever thought was possible.

Why Flight Training Translates to Cyber

In flight training, I’ve learnt that every journey starts long before take-off.

Preparation, awareness, rehearsal and routine shape every decision. I’ve noticed how much this mirrors the world of cyber security. Pilots plan for problems before they happen, knowing that when mechanical or electrical failure hits, instinct and training must take over and handle it quickly.

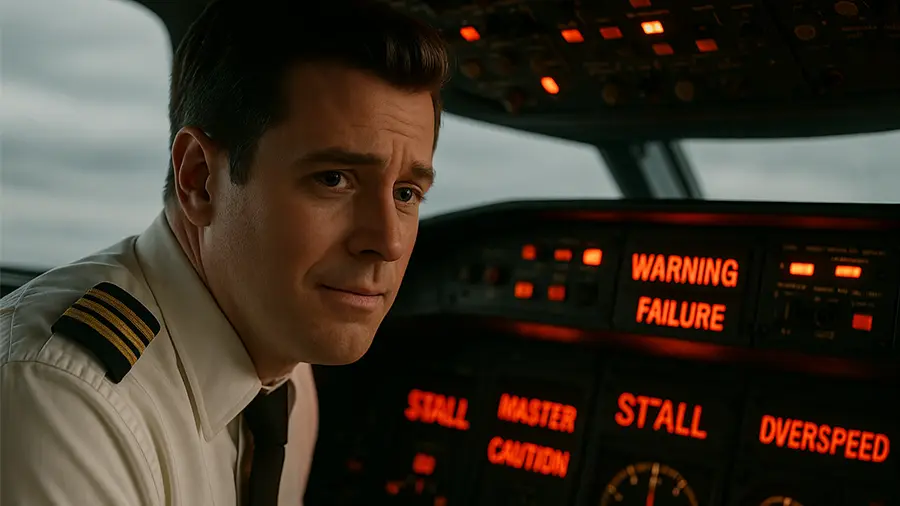

🚨 Managing Cockpit Emergencies

Lesson 1: Failure is Inevitable

When you fly enough, electrical or mechanical failure is inevitable. It might be a faulty fuel gauge, a worn magneto, or a sensor that drifts out of calibration. Aircraft are complex machines with thousands of moving parts, and the longer they operate, the more likely something small will break. That’s not a sign of poor design, it’s simply the reality of engineering plus usage.

It’s the same in the business world. The longer a company operates, and the larger its digital footprint becomes, the odds of a data breach increase to the point of inevitability. More systems, more users and more integrations mean more opportunities for someone to get in, or something to get out.

Just as pilots accept that failures will happen and prepare through training, redundancy and maintenance, growing firms must accept that cyber incidents are part of the journey and must prepare accordingly.

The lesson from aviation is not to aim for zero failure, but to build systems and habits that embed resiliency into everything you do. Routine checks, backup plans and calm responses turn inevitable faults into manageable events, both in the sky and in cyber security.

Flight training normalises emergencies. It makes you rehearse critical failures so much that they become mundane. Fast, calm responses to emergencies fix problems fast. The majority of businesses today happen upon major cyber incidents for the first time when they occur which can compound the impacts they have.

Lesson 2: Necessitate Multiple Control Failures

One of the first lessons in flight school is that redundancy means safety. For both yourself, your instructor as well as the unwitting people on their sofa’s below watching Eastenders oblivious to your soaring above.

Two good examples of control redundancy;

- Dual magnetos: single and twin engine aircraft use two magnetos to power two spark plugs per cylinder so if one magneto or spark plug fails, the other keeps the engine running.

- Main + standby alternators: an alternator is responsible for generating electrical power once the engine is running. Modern aircraft have a standby alternator to power essential radio/comms/navigation instruments if the main electrical system fails.

That idea of building in backups applies directly to cyber, known as adopting a defence-in-depth approach. This means layering controls such as network segmentation > firewalls > Intrusion Detection System > backups all serve as safety nets, meaning that multiple control failures have to happen for a significant impact to the business to occur. If one fails, another catches it. Redundancy isn’t inefficiency, it’s designed resilience.

Redundancy is designed-in resilience. It’s not wasted effort, it’s an essential design principle required to ensure continuity of services in an uncertain world.

👨🏼✈️ Human Performance

In aviation, human performance refers to the capabilities and limitations of people when performing tasks in an operational environment. It’s a core part of aviation safety because even the most advanced tech relies on human decision-making, coordination and awareness.

Lesson 3: “Hours in the Air”

Every flight you do goes into your pilot logbook, and every lesson builds on the last. You can visibly see your experience building and emphasis is placed on “doing reps”, aka flight time or “hours in the air”.

Cyber security needs to work in the same way. If you want to provide a genuinely excellent service, whether that is internally to your organisation or like CyPro as trusted security partner to our clients, we need to do reps. Learn, adapt and repeat until you become a genuine expert in whatever cyber security discipline you are focused on.

This I have found has two effects…

Firstly, it makes whatever you’re doing second nature and therefore makes you more competent in it. Secondly, doing reps increases confidence which then compounds your competence further. Both have a significant positive effect on your overall capability as a pilot, and a cyber security leader.

Lesson 4: Exams & Certifications

There’s a lot of negativity around cyber security certifications like the CISSP, CISM, CRISC, etc. Many say they’re pointless box-ticking exercises. The main criticisms I see are;

- High cost – some of them are expensive. However, there are many that are not and many professionals work at organisations who would gladly pay for them. Granted, some would definitely be hard to pay for personally, but it’s like anything, focus on those which aren’t over-priced.

- Theory over practice – the oddest argument I’ve seen is that many certs test theory rather than hands-on practical skills. Well, yes that is precisely what they are designed for. “Theory” is synonymous with “knowledge” and when you reframe it in those terms, it can be quite dangerous, especially in aviation, to argue that acquiring and testing your level of knowledge is not important.

- “Maintenance tax” Continued Professional Development – I’ve had to do the CPD for decades and it’s a pain but it’s clearly there to weed out those who aren’t genuine cyber security professionals practicing what they preach each day. If you’re “living and breathing” cyber you’ll always have more than enough books read, presentations given, etc. to put into your CPD. It’s a necessary evil.

These are familiar arguments but in my opinion, from what I’ve learned from flying, they are missing the point.

I agree that certifications get misused on entry level job descriptions and that just because you have a whole load of letters after your name it doesn’t necessarily mean you are credible, but this is not what they are designed for. They are merely designed to assure individuals to a standard minimum baseline of knowledge.

In aviation, no one mocks a pilot for passing their (nine) Private Pilot Licence (PPL) exams or maintaining their type ratings. The exams don’t make you an expert pilot, they ensure that everyone sharing controlled airspace speaks the same technical language and understands the same safety rules. In aviation, it would be ‘weird’ if you weren’t able to pass them. I don’t see why cyber security should be any different.

Cyber certifications, when designed properly, simply confirm that a practitioner knows the fundamentals of networking, risk management, cryptography or incident response before being trusted to protect critical systems.

Passing an exam isn’t the destination it’s the minimum proof that a person has the knowledge and understanding to fly safely, for themselves and for others. No one in aviation suggests that exams alone make a safe pilot. They are one component as part of a wider accreditation system (flight hours, simulator drills, refresher flights, biennial flight reviews, handling skills assessment, etc.). Likewise, in cyber, certifications shouldn’t be seen as credentials for ego’s sake, but as markers of assured competence (the start of professional growth, not the end).

The problem isn’t that we test people’s knowledge, it’s that too many in our industry forget why the testing exists. Sure, they’re not perfect but that doesn’t mean they hold zero value. Exams bring a minimum baseline of trust and shared understanding and should be encouraged, not chastised.

Lesson 5: Cognitive Load

I’ve realised how cognitive load is freed up when you practice something until it becomes second nature. In flying you perform something called ‘circuits’ which is practicing the take off and landing of an aircraft. When you do circuits you have the same procedures to follow for every take-off, go-around and landing.

Early on in your learning, it takes all your cognitive power to remember everything that needs to be done and in what precise order. If you don’t lower your flaps before you start making your descent to final approach then you’re unlikely to reduce speed sufficiently for a safe landing.

The same is true in cyber incident response. The first 30 minutes of a major incident shouldn’t be improvised, it should feel automatic. Not only because this speeds up your response, but because it lowers stress (making decision making better) and frees up your grey matter to take in more information as it emerges as the incident progresses. All this comes together to ensure responses are of a higher quality, faster and more repeatable, time after time.

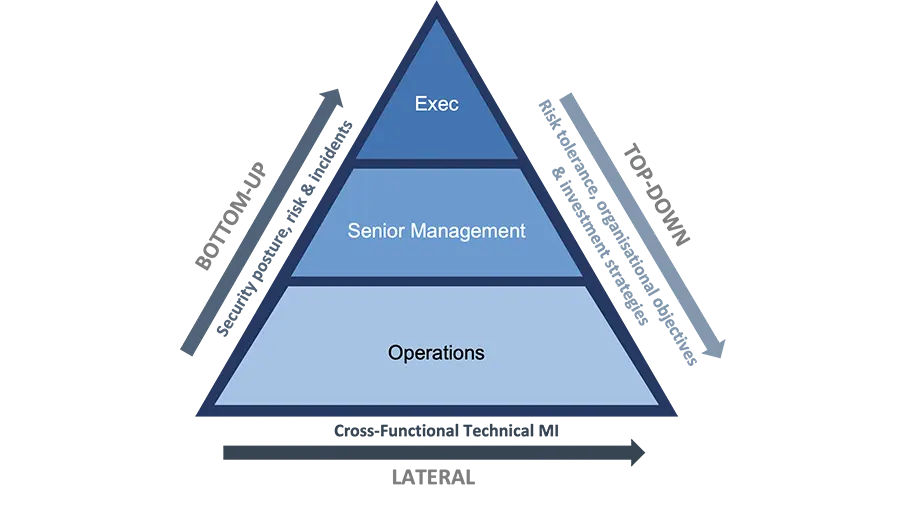

Lesson 6: Communication Discipline

In the air, comms must be short and clear. A single word said wrong can cause confusion. In cyber security, the same rule applies. Clear language and early escalation matter. I’ve learnt that silence or delay is far more dangerous than admitting a problem early.

There are direct parallels one can draw between these three levels of communication (Exec, Senior Mgmt and Operations) and the aviation world:

- Executive <> Navigation systems – tells the pilot which direction to go, their current location and how far it is to the destination. The destination is set by senior management based on the strategic objectives.

- Senior Management <> Altitude, airspeed and bearing – helps the pilot operate the aircraft safely within acceptable limits, headed toward the destination set by senior management.

- Operations <> Fuel, oil pressure, engine temperature – ensure they are within acceptable tolerances to ensure (day-to-day) progress isn’t disrupted by mechanical failure.

The best analogy here is with senior management not getting sight of the vulnerability state-of-play for their organisation. I’ve seen all manner of excuses as to why the exec don’t have this communicated to them but the reason is ultimately irrelevant. Not having this view is tantamount to staying silent on the radio when flying.

It doesn’t matter why you’re not communicating on the radio, people are completely unaware of where you are, where you’re headed or if you’re facing an emergency and as such, no one can help. Communication just stay open, honest and concise irrespective of whether the message is a positive or negative one. Only then can positive steps forward be made.

🧭 The Pre-Flight Mindset

Lesson 7: Checklists Build Reliability

Before every flight, you have to go through an aircraft specific checklist irrespective of your experience. Been in the RAF flying Tornado’s for 20 years? Doesn’t matter. You still have to run through the same checklists as a pilot-in-training. This is because it helps build consistency, muscle memory and reliability into the process of getting into the air.

The same mindset applies to cyber. If you have worked on a patching process so much that you now have a standardised approach, you create consistent behaviour when pressure rises and you know much earlier when things deviate from the norm.

Lesson 8: Automation Aids Safety

Everybody always thinks automation is there to save time. I have found, it is actually more beneficial as an enabler to more effective security controls, not just saving time.

One parallel with aviation here is where I have learnt how Instrument Landing Systems (ILS) provide radio signals that guide the aircraft on the correct approach path (both lateral and vertical). The autopilot can use these signals to perform a fully automated landing. This reduces pilot workload and human error during critical flight phases, and allows safe landings when manual visual reference is impossible (e.g. CAT III conditions which means very low visibility conditions such as dense fog).

In essence, automation has become a kind of co-pilot that never gets tired, distracted or complacent. It quietly monitors, calculates, and corrects in the background, giving humans more capacity to think and make decisions rather than manually wrestling with controls. And while pilots still carry ultimate responsibility, this layered automation gives aviation its incredible safety record, proof that automation, when done properly, isn’t about removing people, but about protecting them from the limits of being human.

The same logic applies in cyber security. Automation isn’t just about efficiency or scaling response, it’s about building sustainable resilience and reducing risk. This is best represented in a SOC (Security Operations Centre) in the case study below.

At CyPro, we have a UK based SOC which operates 24/7 and we use automation to not only make operational processes slicker, but also to catch cyber attacks earlier than a human can.

When our analysts are monitoring client environments, speed matters but accuracy matters even more. In a traditional SOC, analysts rely on manual triage of alerts, correlation across multiple tools and threat feeds, and subjective judgement to decide what’s worth investigating. That’s fine until the volume of alerts spikes, or when a genuine compromise starts to unfold across systems.

We’ve built automated correlation and enrichment workflows that take raw telemetry from EDRs, firewalls and cloud logs, automatically validate the event against known threat intelligence, and prioritise based on business context and threat likelihood. This means that before an analyst even sees an alert, the system has already done the heavy lifting, ruled out false positives, pulled system data, checked user behaviour and mapped indicators to the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

We’ve seen real-world examples where automation has identified lateral movement attempts within minutes, whereas a manual process might have taken hours.

SOC automation isn’t about replacing analysts. It’s about giving them more time to think. By removing repetitive tasks we allow our analysts to focus on what humans are best at — understanding intent, investigating root cause and strengthening the client’s defensive posture. The autopilot doesn’t fly the plane for the pilot, it makes the flight safer by handling what doesn’t require human judgement.

Automation isn’t just an efficiency investment – it actually improves cyber security. It builds consistency, reduces fatigue, and catches threats faster than a human ever could. And just like the safety systems in aviation, it doesn’t remove responsibility, it simply makes the environment more resilient when the unexpected happens.

Lesson 9: Perceived vs Actual Complexity

From the outside looking in, flying looks incredibly complex. The cockpit is full of switches, dials, lights and screens that seem overwhelming to anyone who’s not trained to use them.

There are quite literally hundreds of procedures, radio calls and checklists, all seemingly essential just to keep a few tonnes of metal in the air. But when things go wrong, pilots don’t rely on a thousand-page manual. They are trained to just back to the basics: maintain lift.

Everything else is secondary. No matter how sophisticated the aircraft, flight safety ultimately depends on understanding and managing that one simple truth.

Cyber security suffers from a similar illusion of complexity. Frameworks like NIST or ISO 27001 can look like an aircraft’s cockpit…overwhelming lists of controls, sub-controls and audit requirements. Too many organisations try to switch everything on all at once, chasing the illusion of complete compliance rather than meaningful risk reduction. They get lost in the buttons and dials, forgetting the simple fundamentals that actually keep them safe.

Just as a pilot focuses on two key things (attitude and airspeed) to maintain lift, the best cyber security professionals take their time to focus on a similar set of things;

- A risk-based approach (focus on the things that bring the largest amount of risk reduction)

- Aligning that approach to the threat landscape (focus on the most likely attack vectors for that organisation), don’t try and boil the ocean.

A company that grounds its defences in a clear risk-based approach, mapping the most probable threats/attack vectors (and aligning controls accordingly) will always outperform one that tries to implement every control in the book.

Those organisations who prioritise shear number of controls implemented rather than the type of controls, inevitably will end up with “security theatre” – the illusion of protection but no actual tangible risk reduction in practice. Simplifying isn’t cutting corners, it’s about clarity of focus and return on effort (and budget).

In both worlds, complexity can be seductive. It looks impressive, it feels comprehensive, but it rarely adds safety on its own. The best pilots and the best cyber leaders share the same mindset. They know that when the pressure’s on, success comes from mastering the essentials, not over-complicating things and drowning in the detail.

Conclusion – Maintain Lift

Learning to fly has shown me that complexity doesn’t make you competent, discipline does. Every pilot learns to respect procedure, prepare for failure and think clearly when everything seems to be going wrong. That same mindset applies to cyber security. The best outcomes rarely come from flashy tools, huge control sets or AI enabled tech. They come from clarity, preparation and practice.

Aviation teaches that safety is built on repetition, structure and an understanding of where human fallibility meets system design. Cyber needs that same humility. We can’t patch everything or predict every attack, but we can build defence-in-depth, resilience / redundancy and calm decision-making into how we work.

Both disciplines reward those who think ahead, communicate clearly and never stop refining the basics.

For me, flying has become more than a hobby, it’s a mirror held up to our profession. It reminds me that when the pressure’s on, our job isn’t to look like we are ‘expert’ – it’s to keep the organisation flying: maintain lift.

Contact Jonny – if you’d like to chat to Jonny about his article, please reach out here.